Where the World Doesn’t Reach

Written by: Kaygan Lane

First Published: 15 October, 2025

Content note: Chronic illness, social isolation.

Seven and a half hours.

I spent seven and a half hours outside of my house this fortnight. One baby shower, two work meetings, four dog walks and briefly pushing my wheelie bin to the curb. I did check the mail while I was down there, so that counts as two outings, right?

Three hundred and twenty-eight and a half hours spent in my bedroom. Well, the house plan says bedroom, but this is actually my living room. Not in the traditional sense of the room where your furniture is positioned pointing at the TV like some screen-addicted sundial. No, more in the ‘this-is-the-room-I-do-my-living-in’ living room. Seven and a half hours is quite good for me. Sometimes it’s ten minutes – bending over the doorway, clawing the crinkled brown Coles delivery bags into the entryway. Hoping my neighbours don’t see me. Hope is the gap between what I know is certain (they’ve noticed – my car has been broken down in the garage for most of this year, no need to fix it if I’m not going anywhere) and an optimistic wish (maybe they just think I have a home business making cupcakes?).

It wasn’t always like this. There were times I hopped from coffee with friends, to the movies, and then over to the house of some pretty-blonde woman I met online. It wasn’t always like it is now I wasn’t always like I am now.

I’ve been sick for 10 years. Well, 10 years last March – I should’ve gotten myself a cake and some half-filled balloons in some sad boring beige. I call my sickness my living-limiting disability. Not because it will shorten my life (but I’m sure it will) but because it robs me of most of what a life could experience. Sometimes I just say ‘she’s being horrible lately’ or ‘You Know; The Thing’.

It’s not all bad, but it mostly is. I’ve never had to get a mole removed at a skin check; you’d have to see the sun first. My shoes last a long time.

My friendship circle has dwindled to four. How patient can you expect a friend to be when consistently “I’ll be there!” turns to “I’m sorry, I know this is really frustrating, I need to go to urgent care. I won’t be home in time”.

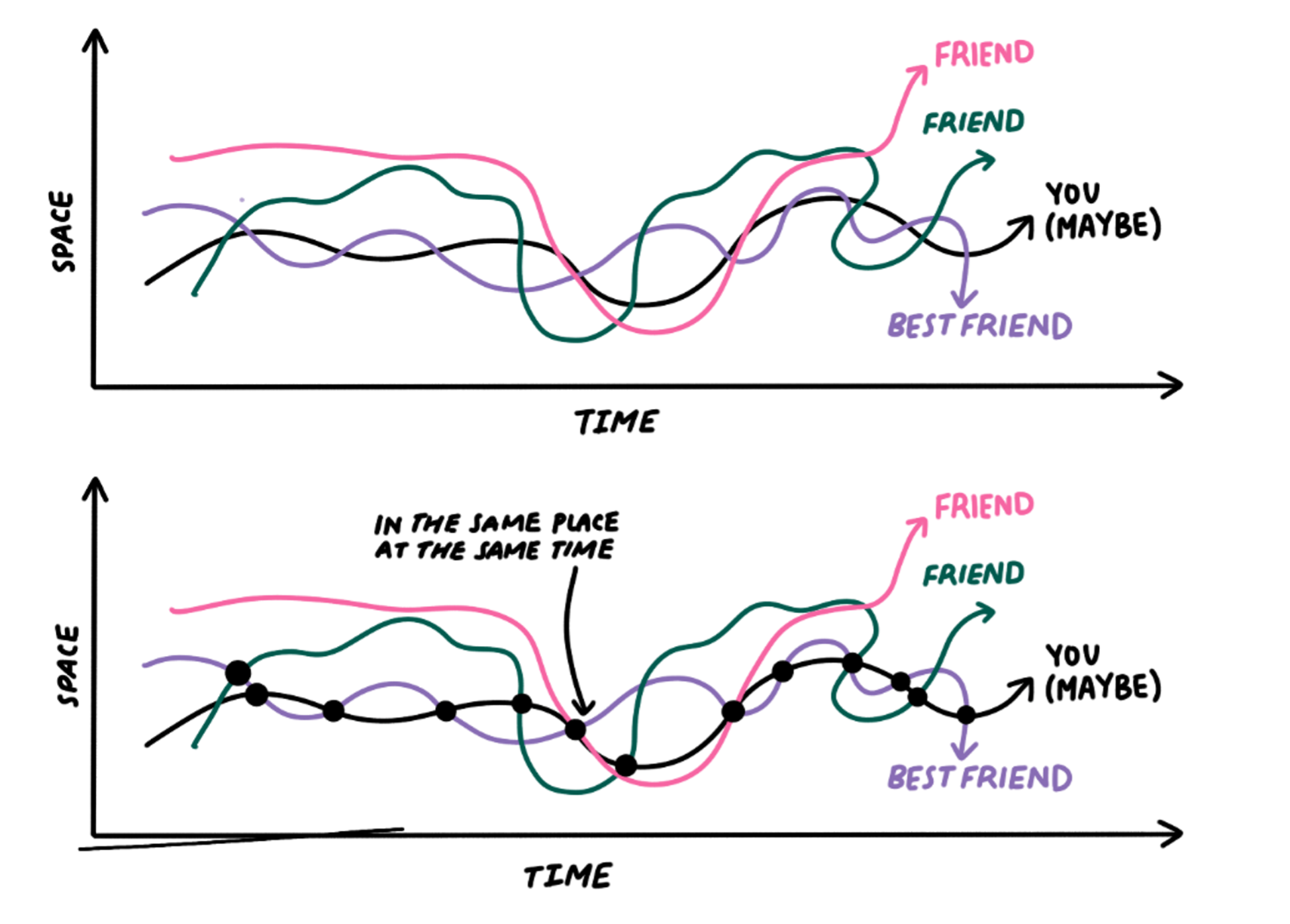

If being non-disabled and having non-disabled friends looks like this:

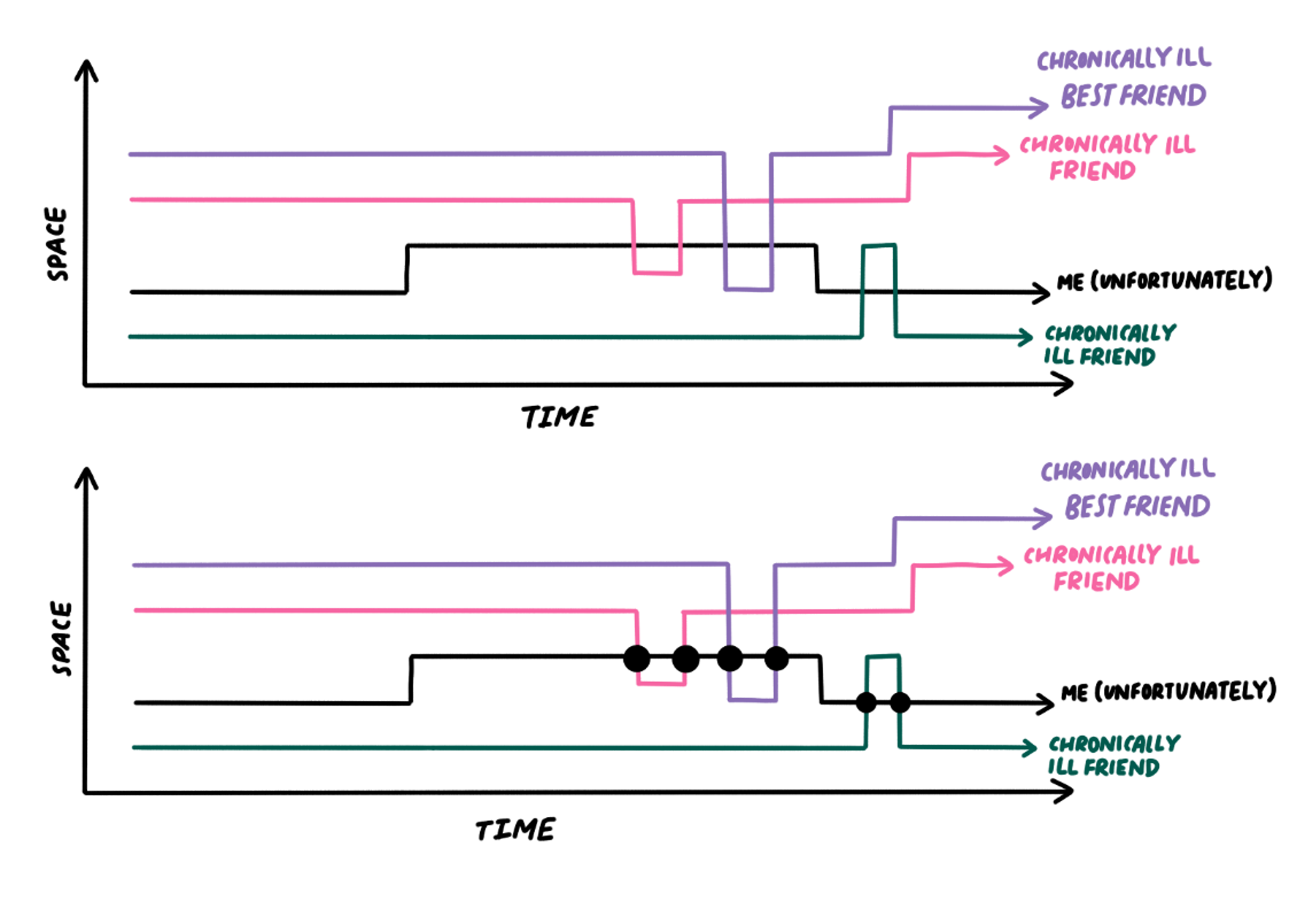

My friendships look like this:

When those lines intercept, when we’re in the same place, we’re pushing organza bags of trinkets and handwritten notes into each other’s arms. Things to open, one at a time, prolonging the sense of togetherness.

The public spaces in which we meet are what sociologists called Third Spaces. Not home, not work, but a secret third thing.

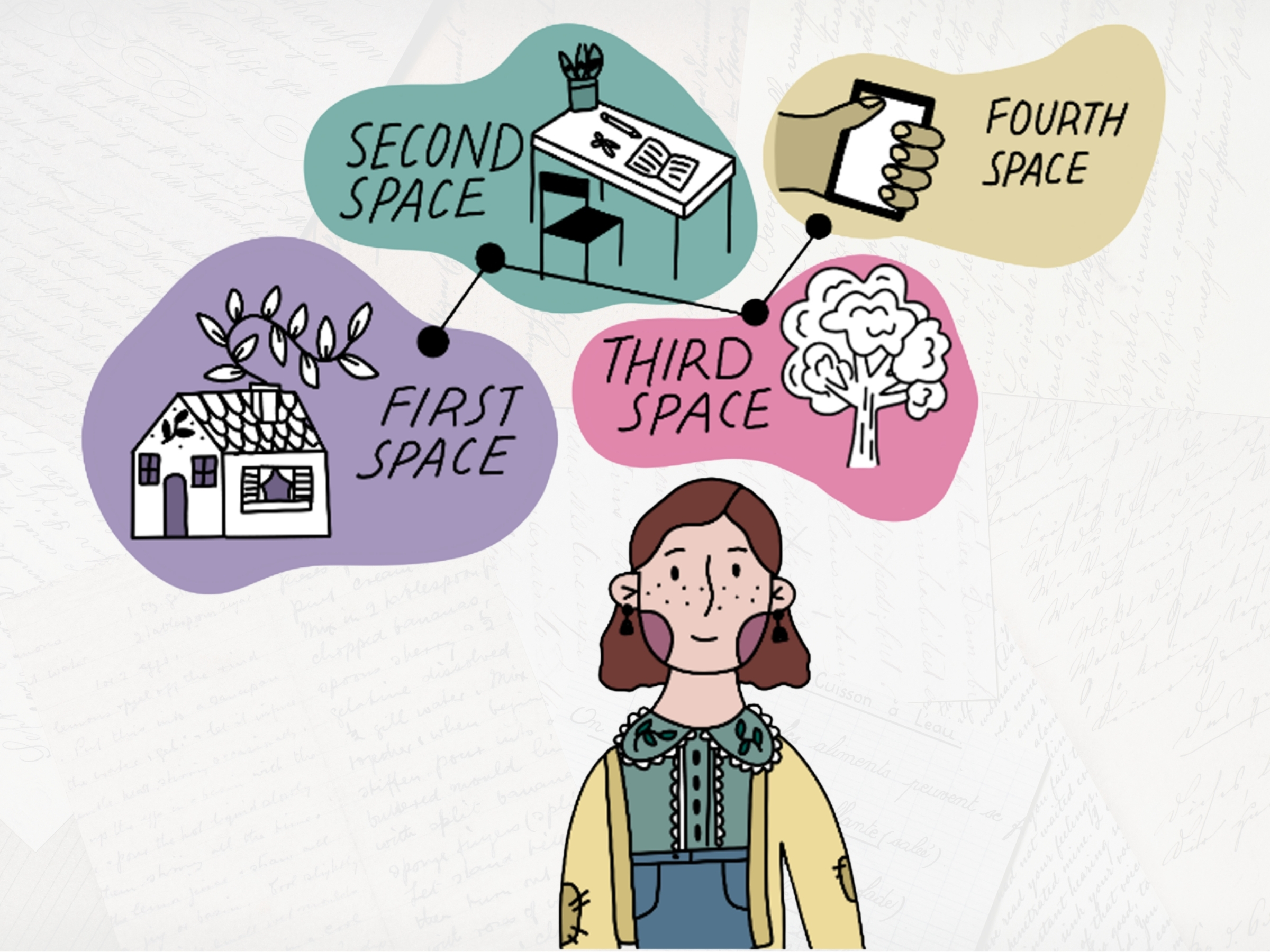

They first gave us First Spaces (home). Then Second Spaces (work) and Third Spaces (parks, libraries, cafes). Fourth Spaces came after (digital realms), which let us attend meetings, and a webinar on snail farming, all from bed.

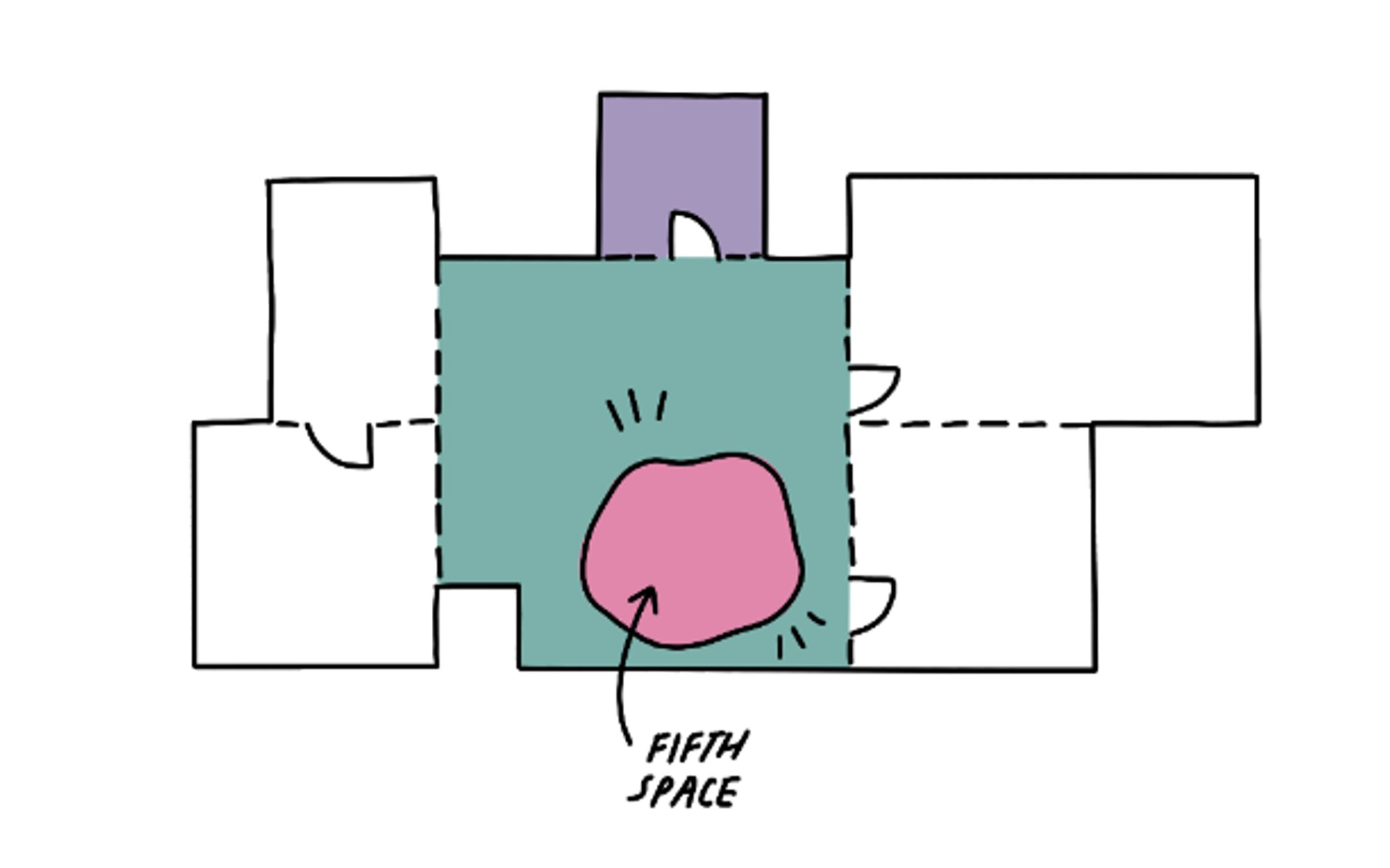

Your Spaces might look like this:

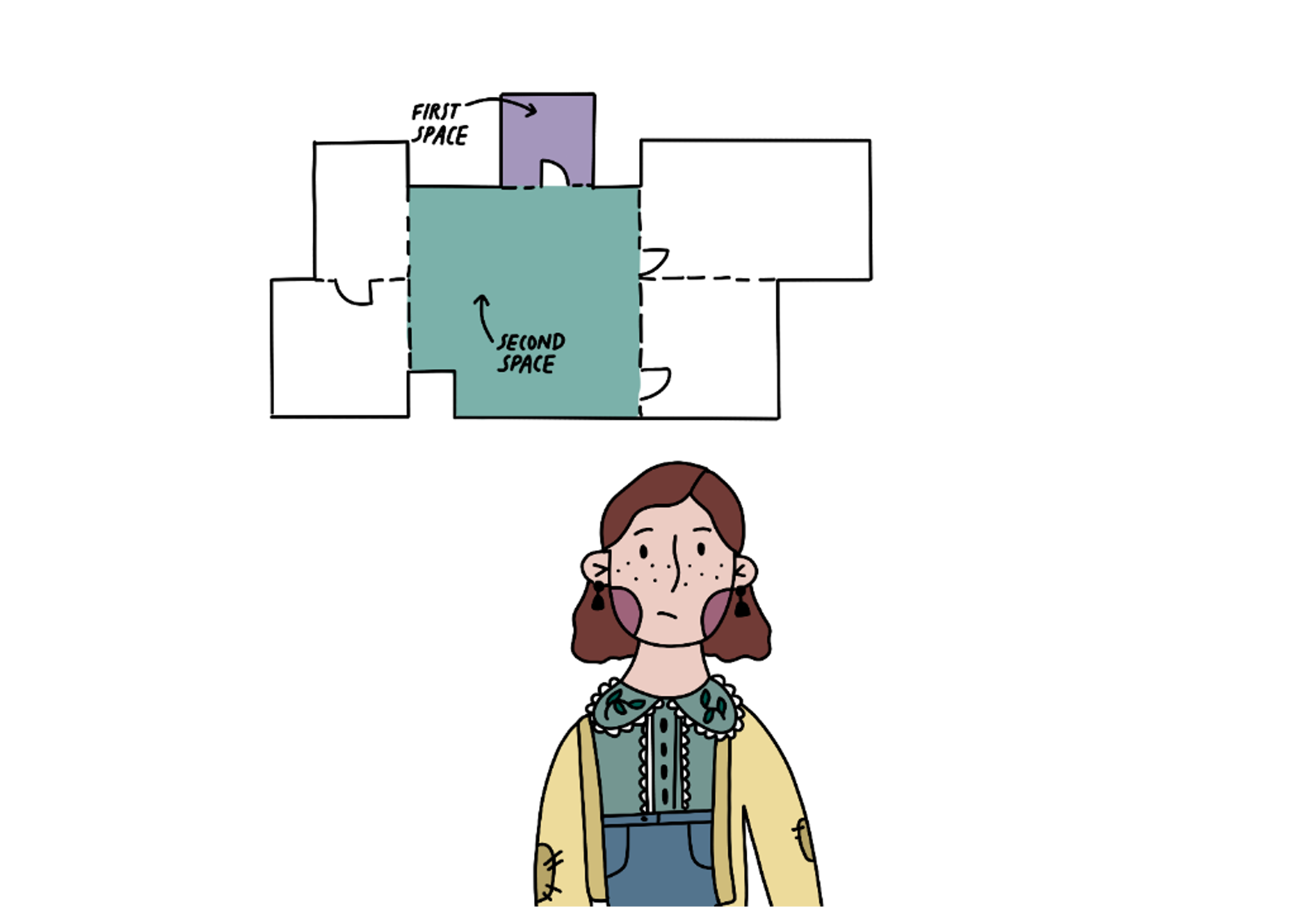

I say that sociologists gave us Third Spaces, but I didn’t get any. I got one. The Space. The Space is my home, my work, and my social space.

For most of my adult life, that felt like a limitation. I was missing out on the world. I didn’t have access to Spaces. The Space had to do everything.

My Spaces look more like this. Small spaces in the same house.

The key to living a disabled life, I think, is reinvention. A relentless rephrasing of your limitations to allow yourself to not sink into defeat. A redefinition of fulfillment. If I’m allowed to be a sociologist for a moment, I would like to talk about how reframing my The Space has created what I call Fifth Space.

Definition: Fifth Space is a space created and separated by time. It’s the same physical space but for a moment, it becomes something else entirely.

Sometimes, my bedroom becomes a café. I put on a YouTube video of ambient café noise, sit at the table with my laptop, and sip coffee from a chipped mug. The light hits the wall just right, and for a moment, I’m somewhere else.

My inbox becomes a community centre. The screen glows with connection. I am not alone.

My living room becomes a cinema. Paper chains draped across the windows, a hot chocolate bar with toppings labelled in glitter pen. I step outside. I pause. And I walk back in, into something else. This is Fifth Space.

Chronic illness doesn’t just reshape our bodies. It reshapes our timelines, our relationships, our sense of self. It can rob us of the rituals that mark adulthood: the steady job, the casual brunch, spontaneity, the dependable energy to show up. It can steal the ease of belonging, access to community, the unspoken promise that life will unfold in a certain way.

Fifth Spaces alleviate a lot of ‘should be able to’s for me. I should be able to experience new things, should be able to do what every other twenty-something does. When those things are taken, slowly, quietly and relentlessly, we’re left with a kind of adulthood that doesn’t fit the mould. One that’s often solitary and invisible.

Fifth Spaces remind me that even when my world feels small, I can choose to see opportunity. It’s about finding ways to live, connect, and celebrate within the limits I didn’t choose.

If Spaces outside your home feel out of reach, you’re not alone. If your days feel small, if your world feels paused, I hope you feel permission to build something softer, something slower, something yours. Fifth Spaces are proof that even in isolation, we can still make meaning. We can still make home.

About the Author

Kaygan Lane (she/they) is a disabled illustrator and visual communicator who turns complex ideas into visuals that are socially responsive and accessible for disabled, neurodivergent, and chronically ill communities. With a love for storytelling, nature, and community building, Kaygan creates artwork that invites connection and sparks understanding. Her community work is integral to her art practice, as it shapes what she makes, how she makes it, and why it matters. She’s been commissioned by organisations like Women with Disabilities Australia, the Youth Disability Advocacy Network, and Children and Young People with Disability Australia to create illustrations that centre lived experience and drive change. Kaygan lives with her wife on Whadjuk Noongar country, where she spends her free time at the park with her senior toy poodle Yuki, rereading Jacqueline Wilson books, and crafting.